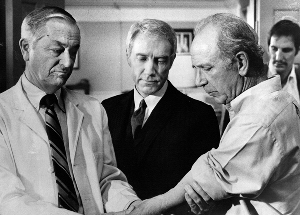

I collect stories of how the doctor/patient relationship has changed over the last half century. There’s a new generation of doctors and patients who’ve only known the 12-minute office visit. For them, an extended, personal conversation between a patient and her physician is as antiquated as Marcus Welby, MD.

I collect stories of how the doctor/patient relationship has changed over the last half century. There’s a new generation of doctors and patients who’ve only known the 12-minute office visit. For them, an extended, personal conversation between a patient and her physician is as antiquated as Marcus Welby, MD.

In the 12 to 15 minutes allotted to a patient, discussion is necessarily limited to the immediate symptoms. There’s no time to understand the context in which the patient lives, works, and loves. For that type of holistic understanding patients seek out alternative medicine, which they do in increasing numbers. Now that anti-depressants are more cost-effective than talk therapy, conventional vs. alternative medicine is the new division of labor.

Consider how the meaning of the word “personal” has changed when applied to medicine. Today “personalized” medicine does not mean time for the doctor to better understand the individual patient. It means using more technology. The definition of “personalized medicine” in the 2007 Senate bill is “the application of genomic and molecular data to better target the delivery of healthcare, facilitate the discovery and clinical testing of new products, and help determine a person’s predisposition to a particular disease or condition.”

We can never return to a simpler, slower, less technological past, nor would we want to. Cancer vaccines, genomic sequencing, and stem cell research will lengthen our lives and improve the quality of our days. I’m not convinced, however, that the modern doctor/patient relationship is progress. Medicine is still about healing, and listening to the patient remains a highly therapeutic process.

Hiding in clinical foxholes, far from the essence of the patient

I recently came across a story from Dr. Paul Rousseau, whose email address is “palliativedoctor.” He advises patients and their families on end-of-life care. He discussed a woman, Mrs. Albersmith, who was ready to die. She had an advance directive, the quality of her life had become unacceptable to her, and her family was in agreement.

Dr. Rousseau spent time talking to Mrs. Albersmith’s sons, grandson, and husband. Not only did he ask about his patient’s life, but he asked about her husband. He was amazed to learn that this man had helped develop the GPS system for the military and that William Buckley had wanted to purchase one his sculptures. Speaking to other doctors, he comments:

As I bid Mrs. Albersmith and her family good-bye, … I wondered how often a physician fails to understand the value and importance of a family member, especially a husband or wife, especially at the end of life. This person is an integral part of the patient’s personal, cultural, and spiritual makeup, and his or her history helps to develop a clinical portrait of the patient’s values and beliefs. … Unfortunately, I believe such clinical absences – the failure to acknowledge and to collect the history of a close loved one/caregiver – occur more often than not. …

It seems that we physicians have strayed from the bio-psychosocial model of patient care as well as the humane and personal touch that is so essential to healing and instead have chosen to hide in clinical foxholes where CT scans, laboratory data, and mundane and tangential information is discussed, far far from the bedside, and far far from the essence of the patient.

Related posts:

The indignity of the waiting room

Doctors in the trenches speak out – Part two

Contempt and compassion: The noncompliant patient

Sources:

(Links will open in a separate window or tab.)

US Senate, Text of S. 976 [110th]: Genomics and Personalized Medicine Act of 2007

Paul Rousseau, MD, The Other Person, The Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 302 No. 8, August 26, 2009 (subscription only)

Margalit Gut-Arie, The End of Dr. Marcus Welby, The Health Care Blog, May 4, 2009

Interesting post that reflects appropriate disappointment on my profession. As a holistic family physician, I’m still having fun learning about life from the people who are my patients. Their humanity feeds my humanity and that of all fellow humans. My most important job is to let them know that they matter and mattering is in their own context. This is very rewarding.

My practice takes “Families Only” and that is also enriching to them and me.

Many family physicians still connect well to the humanity of their patients and help the patient to stay connected to or reconnect to their own dream. Physicians employed by non-physicians have more challenges getting to relate to the wholeness of their patients. The business culture of hospitals and the Medical Industrial Complex is crushing the human aspect of medical practice.

Your writing is important to help with our understanding of what is happening. I just discovered it through your post on KevinMD. Thanks

Thanks so much for your comment, Dr. S. I know there are many wonderful family physicians out there who don’t get flashy publicity, but who are sincerely appreciated by their patients. I’m grateful to JAMA for printing stories of the doctor/patient relationship in their weekly feature, A Piece of My Mind.

I’ve been watching the TV series Marcus Welby, MD. It’s been unavailable all these years, but was recently released on DVD. (Season One is out. Season Two comes out in October.) In the pilot episode, Dr. Welby gives a very moving speech to a group of young hospital residents on the rewards of being a general practitioner, rather than a specialist.

Welby is a family physician. He often comments on how he has known a patient since they were born. He uses his knowledge of the whole family not only to help the patient, but to help the family, who are of course affected when one of its members has a medical problem.

What’s striking by today’s standards is how much time he has for his patients. He drives 60 miles to see a man who failed to show up for an appointment. He stays up all night in the hospital questioning whether there’s anything more he could do.

He sets a standard that’s impossible under today’s conditions of health care. There are aspects of his practice, however, we wouldn’t want to return to. The episodes are a graphic illustrations of what’s meant by doctors being “paternalistic.” Also of the automatic authority the profession received. Medicine has changed to empower the rights of patients. When I watch how women were treated in 1969, I’m grateful for some of these changes.

There’s no going back. What’s been lost, however, is the healing power of a doctor who’s willing and eager to listen to a patient, to appreciate and understand the whole person. An excellent book on the subject is Edward Shorter’s “Bedside Manners: The Troubled History of Doctors and Patients.” Shorter is a medical historian.

Thanks again for your comment.

Dr H,

I loved Marcus Welby and Dr Kildare as a high school student who decided to be a family doctor. Later I met Tom Stern (House Calls is his biography 2000 BookPartners) who was the family physician advising Dr Welby and his writers/producers representing the AAFP. Bob Young, MD, a friend practicing solo in Johnstown, OH, also advised the show and had many of the attributes of Marcus Welby including the paternalism.

Times have changed, but relationship based medical practice is still the heart of Family Medicine. Part of the reason we’re taking such a hit from the MIC is that we’re lovers, not fighters. Our patients deserve the revolution that we haven’t yet discerned. Peace

Dr S,

I love that thought – “Our patients deserve the revolution that we haven’t yet discerned.” Much food for thought there.

At the end of the Marcus Welby episodes, there’s a screen that says “Produced with the cooperation of the American Academy of General Practice.” I went looking for that organization and it doesn’t seem to exist anymore. It appears to have merged into the AAFP in 1970. But now there’s also an American Academy of General Physicians.

I’m sure you know much more about this than I do. To me, family medicine is a specialty and a GP is what they call a doctor in the UK. And in the UK, I gather they don’t call doctors “physicians” unless they’re specialists, whereas I tend to use the terms interchangeably, just for variety.

Anyway, Welby was a real family physician, even if the term hadn’t been invented yet. It’s interesting that you know doctors who were advisers for the show. There’s not a lot of technical medical jargon or fancy procedures in the episodes, the way there is in medical TV shows today, but someone sure did a good job of presenting a very positive image of family medicine.